A two-story residence, sitting on an irregularly shaped concrete base and supported with five strategically imbedded caissons, was built with a steel frame prefabricated by a company called Eco Steel, helping to avoid the waste prevalent on most construction projects…

A transcendent perch in the Silver Lake Hills

EcoSteel was featured in the LA Times in June of 2013.

Original Source: LA Times

Written By:

Every house is a reflection of its owner. Some owners are just a bit more complicated than others. Tim Tattu is still settling into his new house, designed by Los Angeles architect Tom Marble in the steep hills overlooking the Silver Lake Reservoir. It is an explosion of angles, steel and outsized ambition. But the house is also filled with small spaces, contemplative moments and simple materials. It’s an epic study in contrasts, as is Tattu himself.

Tattu grew up in Hermosa Beach, studied art in the early ’90s at Art Center College of Design in Pasadena and at the prestigious Städelschule in Germany, and eventually became a set decorator for music videos and TV commercials. But after a few years of partying with stars of the rap and adult entertainment worlds in his old house, also in the Silver Lake hills, Tattu left that life all behind in 2000 to become a monk at a monastery in Okayama, Japan.

“I felt I belonged there. It was just something you feel in your bones,” Tattu said of his decision to throw away his old, hedonistic life in favor of prayer, chanting and hard labor.

In 2007 he finally came back to Los Angeles by way of Whidbey, an island north of Seattle, where he had helped start another monastery and developed a passion for caring for the dying. He now works as a nurse at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center’s palliative care unit, tending to those dying of leukemia, HIV-related illnesses and other diseases.

Tattu planned for the new two-bedroom, 2 1/2-bath house to be an extension of this new life, a stark, simple retreat sited inconspicuously on the hillside. He stressed that he wanted it to be made with a minimum of waste and effect on the Earth.

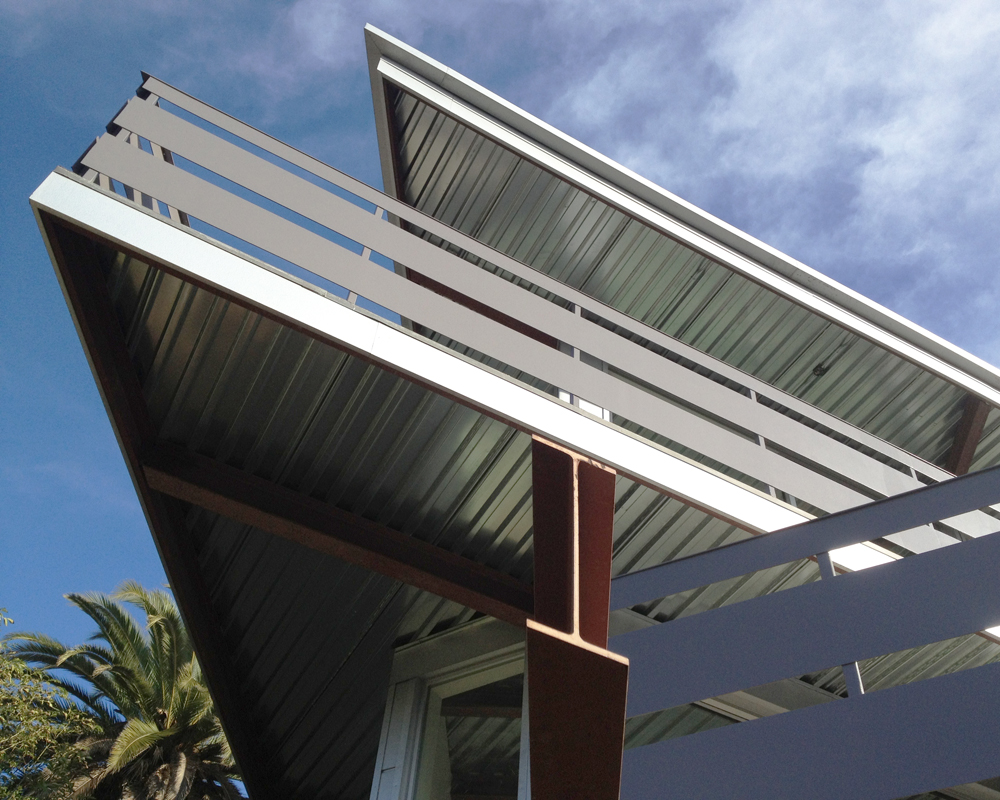

The two-story residence, sitting on an irregularly shaped concrete base and supported with five strategically imbedded caissons, was built with a steel frame prefabricated by a company called Eco Steel, helping to avoid the waste prevalent on most construction projects. Although the project took about a year to build, the steel took only about two weeks to go up. Beyond the omnipresent exposed structural steel (which makes mesmerizing geometric ceiling patterns), the home’s off-the-shelf materials are simple: galvanized aluminum, dry wall, Douglas fir and polished concrete floors over metal pan decking. There’s no imported marble here, no designer chandeliers.

Its intimate interiors, full of built-in storage and shelving to make the most of every odd angle and alcove, are spartanly furnished and decorated. A few of the smaller, more cloistered spaces are designed specifically for meditation. Architect Marble even built a large walk-around balcony on the second floor and a path outside the first to give Tattu space for the traditional Buddhist ambulatory.

But from the beginning Tattu was clear that he didn’t want a plain rectangular building. “I thought, ‘That’s just so boring,’” he said. “I wanted dimension. I didn’t want something flat.”

“He’s not laidback when it comes to design,” noted Marble, who calls the home the Tattuplex. It’s apparent that Tattu’s wild, artistic side was in direct conflict with his humble, spiritual one.

The first proposal was for two attached hexagons. From there the designs just took off, the architect going through more than 90 shape iterations, pushing and pulling with Tattu, who still marvels at the patience of his contractor, Ken Stack.

The variations ultimately provided more varied spaces, more vistas and more fresh air. They, of course, make the home less predictable. The house measures only about 1,900 square feet, but surprises seem to be around every corner: a view of the San Gabriel Mountains or a pleasant breeze coming from a direction you never thought possible.

Several small rooms on the first floor seem to jut in 10 directions. The largest uninterrupted view isn’t the cove-like living room but rather the master bedroom, which makes sense when you imagine Tattu awaking every morning with a panorama of the reservoir.

Because the property is zoned as a duplex, the second floor is actually a self-contained studio with kitchenette, bathroom and laundry. The ceiling is taller, the view even more impressive.

Tattu is still figuring out in which room he will settle. The other he will rent out or leave for visitors, like his roshi, or Zen master, from Japan.

Much of the house reminds Tattu of a ship, from galley-like hallways and bathrooms to the top-floor balcony, which juts off the edge of the house like the Titanic. Marble too noticed this development, subbing out solid railings on the balconies with steel railings with horizontal gaps found on most boats.

Tattu is amazed with the house, noting that it suits the Buddhist quest for the sublime if not its desire for simplicity. He’s still in shock at the not-so-humble elements as well as a final price tag that has approached $1 million, an expense covered partly by the sale of his previous house, by his expected rental income and the low cost of the lot, only $190,000. The process has even altered his relationship with Buddhism. He said he became so obsessed with the house that he had less time for his intensive meditation. He’s also been focused on a new relationship and on his demanding job.

“I can only pay attention to so many things at once,” he said. “You’ve got to let things change. Different things become important at different times.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.